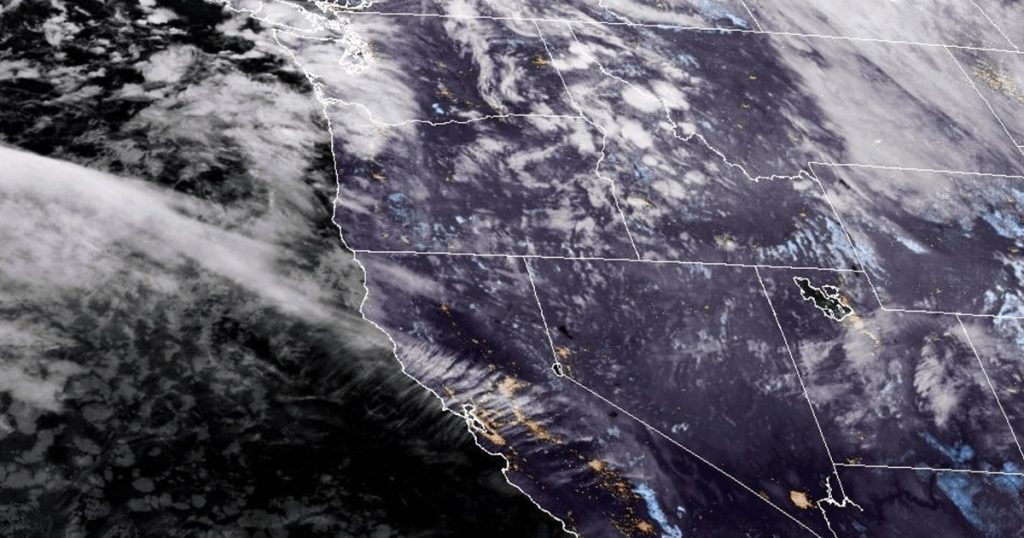

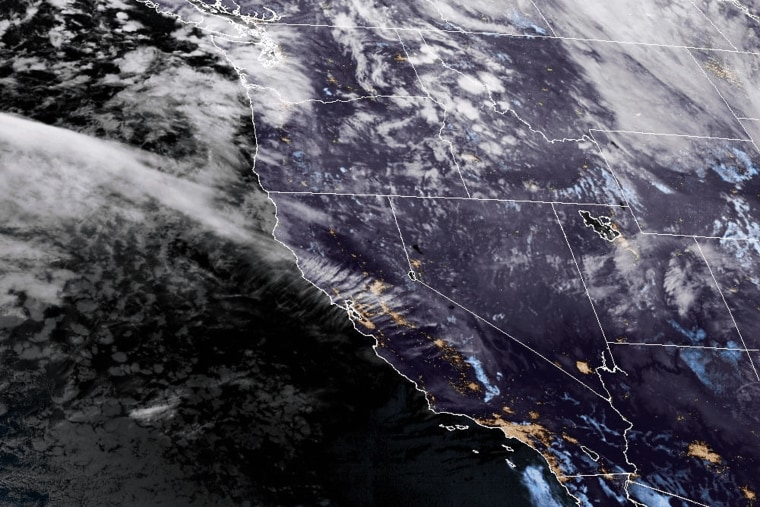

Tens of thousands of homes in Washington state lost power Tuesday and downed wires or trees locked some highways as Northern California and the Pacific Northwest started feeling the effects of a powerful atmospheric river event, officials said.

The storm could bring up to 15 inches of rain and heavy snow in the mountains, forecasters said. By around 7 p.m. local time almost 100,000 homes and businesses were without power in Washington, as well as more than 14,000 in Oregon, according to the tracking website poweroutage.us.

“We are expecting near-hurricane-force winds near the coast with hurricane-force wind gusts over the capes and headlands,” said Connie Clarstrom, a National Weather Service meteorologist in Medford, Oregon.

Forecasters said a whiteout blizzard could hit parts of the Cascade mountains, which run along the spine of the West Coast. The storm could dump as much as 2 feet of snow in Mount Shasta City in Northern California. Because the city is along Interstate 5, that could foul traffic.

Meanwhile, gusts of wind could hit 90 mph on the summit of Mount Rainier, at an elevation of 14,411, in Washington state. Seattle–Tacoma International Airport recorded a gust of 52 mph Tuesday evening, the weather service said.

The fierce winds are driven by a so-called bomb cyclone, or bombogenesis, a phenomenon in which a storm system rapidly intensifies as air pressure drops. A storm qualifies as as bomb cyclone when pressure drops by 24 millibars in 24 hours.

“This one was predicted to deepen, more like 60 millibars in 24 hours, which is obscenely fast and very unusual,” said Marty Ralph, the director of the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes. “It’s exceptionally intense.”

The bomb cyclone will usher in a long plume of moisture from the tropical Pacific known as an atmospheric river.

Atmospheric rivers can be the primary drivers of annual precipitation for the West Coast, and they cause more than $1.1 billion in yearly flood damage on average, according to research published in 2022. Some 84% of flood damage in Western states is associated with atmospheric rivers, research suggests.

Scientists think climate change is influencing atmospheric rivers. A warmer atmosphere can absorb more water vapor, which gives the storms the capacity to deliver more intense precipitation.

“The warmer the air is, the more water vapor it can hold, and that’s more potential energy,” Ralph said.

Over three weeks from late 2022 into early 2023, California was battered by nine atmospheric river storms, which caused widespread flooding, landslides, downed trees and wind damage. Moody’s RMS estimated total U.S. economic losses to be $5 billion to $7 billion from that sequence of storms.

Northern California will likely receive the majority of this storm’s moisture.

“Its main characteristic is strong and stalling. Those two things combined can produce 10 to 20 inches of rain over three days,” Ralph said.

Flood watches have been issued in the northern and central Sacramento Valley, Shasta County and western Colusa County from Tuesday morning through Saturday.

Ralph said the Russian River could receive about 10 inches of rainfall — about 20% of its annual average rainfall — in just two to three days. Some minor flooding is expected along the river.

Several other rivers in Northern California, including the Eel River, could see minor and moderate flooding, according to the National Water Prediction Service.

“The bigger rivers are less likely to flood. It’s still early in the season and the landscape is relatively dry,” Ralph said. “We’re a little bit fortunate.”

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA, said there was a 10% to 20% chance that some areas north of Santa Rosa, California, and into southern Oregon would receive record three-day rainfall as a result of the storm.

“In some places, it will more or less rain continuously from about right now through Sunday morning at least,” Swain said in a Tuesday afternoon briefing. “This looks like a more extreme rain event than it will be a flood event.”

While atmospheric rivers can bring chaos in fall and winter, they’re important for boosting the water supplies in California and other western states. The storm will fill reservoirs and begin to replenish groundwater depleted during a hot summer.

“That’s the story of California water, and the west in general, feast and famine. Big storms come both as hazards and benefits,” Ralph said.

Ralph and other researchers built a 1-5 scale to rate atmospheric rivers striking the West Coast, based on their expected duration and the peak amount of water vapor they transport. In Northern California, the storm is expected to rate as an AR 4 in most locations.