Celena Henry says she lost count of how many times her abuser hit her in the head but remembers vividly when she decided to leave him.

“My feet left the floor, my body slammed against the wall, and I slid down to the floor,” Henry, now 47, recalled. “My head had, I remember, hit off the cabinet, and it made things a little spinny.”

Henry could hear her two young sons crying out, “Don’t hurt mama,” on the other side of the door. She remembers focusing on their cries because she thought it was going to be the last time she heard them.

Then she blacked out. When she regained consciousness, she took the boys and left.

In the years that followed, Henry began to experience persistent headaches, difficulty concentrating and memory problems. While working as an advocate for victims of domestic violence herself, she was attacked by someone else’s abuser and her symptoms got worse, particularly trouble with her balance.

For seven years doctors couldn’t figure out what was wrong until, at West Virginia University’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute’s Concussion and Brain Injury Center, she was finally diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury related to the years of repeated blows to the head.

“It was a relief to have a diagnosis, and for the first time in this whole process of getting ill, having to stop working, I had hope, and I hadn’t had that before,” Henry said.

There’s been growing awareness of traumatic brain injury in sports, but TBI among victims of domestic violence is often overlooked and misdiagnosed, experts say.

Nearly 1 in 4 women have experienced domestic violence, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS), and studies estimate that up to 90% of those women have had at least one traumatic brain injury. National research about brain injury and domestic violence is lacking.

“We don’t have general population data,” said Rachel Ramirez, director of health and disability programs and founder of the Center on Partner-Inflicted Brain Injury at the Ohio Domestic Violence Network. “But pretty much every single study that has been done with an organization that has domestic violence in its name or in its mission has very, very high rates of head injuries.”

Ramirez’ own research found that over 80% of survivors surveyed at domestic violence services report abuse, including hits to the head, and strangulation, which can lead to a brain injury.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office released a report in 2020 recommending that the Department of Health and Human Services improve federal data on the prevalence of brain injuries among domestic violence survivors.

Shannon Legeer, who is on the GAO’s health care team and worked on the report, said it’s important to know how common brain injury is among survivors.

“A key part of understanding what actions need to occur is understanding the magnitude and how it relates to all the other important public health needs that we have in our country,” she said.

After a concussion, the brain needs time to recover, said Dr. Javier Cárdenas, director and founder of the West Virginia brain injury center.

“These individuals get hit, and then they get hit again, and their symptoms get worse and they have the potential for swelling of the brain, bleeding of the brain,” Cárdenas said. “They never have an opportunity to recover, and they are more likely to have permanent deficits as a result of these repeated head injuries.”

A domestic violence victim with TBI can’t get help if doctors don’t recognize or screen for it. A 2011 study found that nearly 80% of domestic violence survivors who report incidents to the police seek health care in emergency rooms, but most are never identified as victims of abuse. A 2021 University of Nebraska study discovered that many never receive medical treatment for traumatic brain injury.

Shireen Rajaram, an expert in intimate partner violence at the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s College of Public Health and a lead author of the 2021 study, blamed a lack of awareness at all levels, including among health care workers and domestic violence service providers.

“It’s just missed over and over again,” Rajaram said. “Women might have other pressing needs when they access services at community organizations, they might need a protection order, they might need housing, they might need services for their children. And so answering questions about getting hit on the head, especially if you have very little awareness of this issue, is not a priority.”

Dr. Ryan Stanton, an emergency physician in Kentucky and a board member with the American College of Emergency Physicians, said brain injuries are easy to miss.

“There is screening in most emergency departments, often at triage,” said Stanton, but “the challenge with intimate partner violence is it’s very rare did somebody come in with that as a their chief complaint, so you have to be able to pick up the signs, the things that don’t make sense.”

Denver Supinger, the director of advocacy and government relations at the Brain Injury Association of America, said that it can be difficult to diagnose brain injuries because symptoms can emerge after an initial trip to the hospital. Victims may not realize it until they can’t work because of light or noise sensitivity or problems speaking.

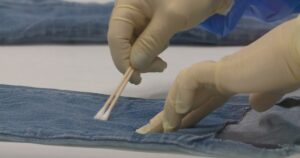

At WVU’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, where Cardenas is director of the Concussion and Brain Injury Center, doctors work with the ER and local domestic violence centers to improve screening and refer survivors for treatment at the clinic. The specialized program treats domestic violence patients as VIPS, giving them priority access to treatments like float and light therapy to promote healing, as well as vision, balance and physical therapy. Some of the treatment rooms look like they belong in a spa.

“Anywhere a domestic violence survivor goes, there should be some sort of screening for a concussion and brain injury,” Cardenas said.

Henry said that she feels physically and emotionally better after receiving treatment at the center. “It gave me a little more power in a situation that I felt powerless with.”