The Food and Drug Administration is changing the way food companies can claim their products are “healthy.” Fortified white bread is out, and fatty fish like salmon is in.

Most everything in the grocer’s produce section — whole fruits and vegetables — would qualify under the new rule issued Thursday. Other nutrient-rich foods, such as whole grains, dairy, eggs, beans, lentils, seafood, lean meat, nuts and seeds also pass the test as long as they have limited added sugar, salt and saturated fat.

Frozen and canned fruits and vegetables are included in the new “healthy” category.

It’s an attempt to help shoppers in other aisles confused by nutrition fact labels that don’t give any real-world guidance as to whether one product is better than another.

“Now, people will be able to look for the ‘healthy’ claim to help them find foundational, nutritious foods for themselves and their families,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, wrote in a media statement.

Nutrition experts were largely encouraged by the change.

“It’s a terrific advance,” said Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, a cardiologist and director of the Food is Medicine Institute at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University. “For the first time, FDA will be judging foods not based on a handful of negative nutrients like calories or fat or salt, but on whether the food has healthy ingredients.”

The previous rule set in 1994 had a cap on total fat, which excluded products with heart-healthy fat, such as avocados. Products could also qualify if they had at least 10% of the daily value for certain vitamins, calcium, iron, protein or fiber.

Manufacturers found a loophole.

“That led companies to fortify junk food and call them healthy,” Mozaffarian said. Fruit juice could be labeled as “healthy” if they had enough vitamin C, for example, despite a tremendous amount of added sugar.

The new regulation eliminates that criteria. Products that can no longer claim to be healthy include fortified white bread and highly sweetened yogurts and cereals.

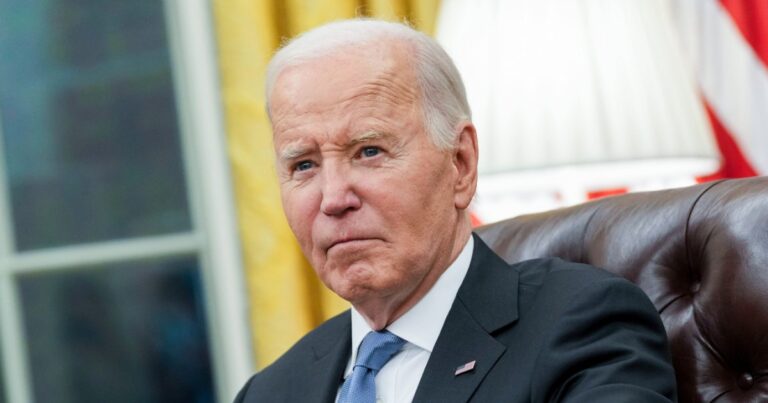

It’s one of the final moves from the Biden administration, and one that’s likely to be embraced by the incoming Trump administration.

The president-elect’s choice to lead the Department of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has repeatedly said that replacing ultraprocessed food with healthier alternatives should be a priority to reduce chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes.

The changes won’t happen overnight. The FDA has given companies until 2028 to comply.

Still, shifting away from that nutrient-centric approach is good for consumers, experts said.

The idea reminds Elisabetta Politi, a dietitian at the Duke Lifestyle and Weight Management Center in Durham, North Carolina, of growing up in Italy where meals were considered “sacred.”

Quality of food mattered more than the number of carbs in a pasta dish, for example, she said.

“When we fix dinner, we don’t think of carbohydrates and fat. We think of broccoli and chicken, maybe quinoa,” she said. “It’s so much more relatable.”

How is ‘healthy’ defined?

One impetus for changing how “healthy” is defined occurred in 2015, when the FDA sent a warning letter to the makers of Kind fruit and nut snack bars. The company, the FDA said, couldn’t claim their bars were healthy because they contained too many calories and saturated fat.

The company pushed back, saying those calories and fat content were because of the nuts in their products, which have proven benefits because of their higher levels of heart-healthy fat.

The FDA agreed, and started the process to update what “healthy” should mean on food labels.

Nearly a decade later, the FDA now says the updated “healthy” rule is in line with current U.S. dietary guidelines and “include a focus on the importance of healthy dietary patterns and the food groups that comprise them, the type of fat in the diet rather than the total amount of fat consumed, and the amount of sodium and added sugars in the diet.”

The FDA is also working on a healthy symbol that companies can add to packaging. Nutrition labels currently in use have not been shown to make a difference in consumers’ awareness of nutrition or how well they eat. The agency says that 75% of Americans lack adequate levels of fruit and vegetables in their diet.

“The updated definition should give consumers more confidence when they see the ‘healthy’ claim while grocery shopping,” Nancy Brown, chief executive of the American Heart Association, said in a statement. “And hope it will motivate food manufacturers to develop new, healthier products that qualify to use the ‘healthy’ claim.”

Brown also encouraged the FDA to move forward with another rule that would put key nutritional information on the front of packages.

And some experts worried that people might rely too much on a new “healthy” label from the FDA.

“Dietary needs are specific to each individual,” said Fran Fleming-Milici, director of marketing initiatives at the UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy & Health. “A ‘healthy’ claim on a package may actually prevent consumers from looking further into the nutritional content and other ingredients that may not be right for them.”